On Monday, the film industry lost one of its most influential figures. John Singleton wasn’t the first to make movies with predominantly black casts but he was amongst the first to tell our stories on the big screen. He didn’t hold back or try to pretty things up. He gave us all the grittiness, violence, despair, hope and hopelessness, poverty, depression, growth and realizations of living and surviving in the urban black community. And he did it with such artistic genius that everyone, no matter their background, could understand and follow the story.

On Monday, the film industry lost one of its most influential figures. John Singleton wasn’t the first to make movies with predominantly black casts but he was amongst the first to tell our stories on the big screen. He didn’t hold back or try to pretty things up. He gave us all the grittiness, violence, despair, hope and hopelessness, poverty, depression, growth and realizations of living and surviving in the urban black community. And he did it with such artistic genius that everyone, no matter their background, could understand and follow the story.

A John Singleton think piece seems out of place for this page on the surface but it is more fitting than anything I’ve ever written. Singleton eloquently describes the breeding environment for many athletes. He tells a story that many of us have heard or experienced. Christopher Wallace told the world “Either ya slinging crack rock or you got a wicked jump shot” and for many young, black boys and girls this is a harsh reality that they must try to safely navigate. Naturally choosing the former rarely ends positively. And oftentimes, the former unfortunately deters success in the latter. But through all the anguish and melancholy of growing up in these conditions, something magical happens for athletes. They become a protected class.

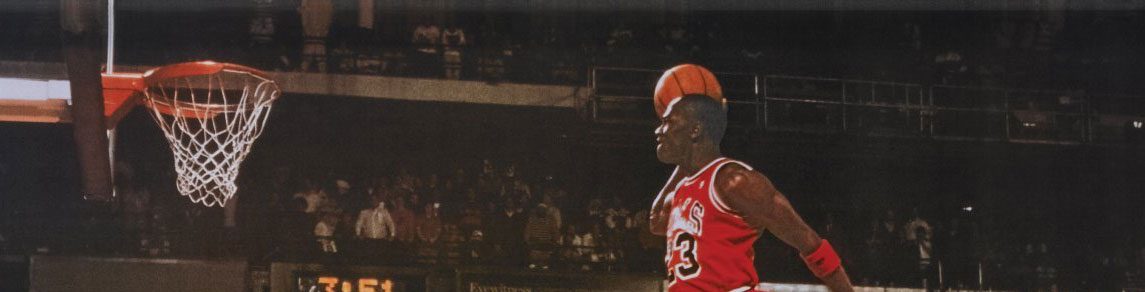

They become the beacon of hope for all of those who have had to resort to a life of drug dealing, gang culture and other pitfalls of urban society. Contrary to popular belief, these people do not celebrate their lifestyle. They long for an escape from it or wish they could do things differently. So when they see one of their own with the opportunity to rise above their circumstances, often through sports, they play their part in shielding them from the same dangers to which they have succumbed. As a matter of fact, let me be explicit in this. It’s not athletes, it’s basketball and football players. There are many reasons for this. Basketball and football are the most accessible sports to inner city youth and they most closely reflect the physicality, flair and “glamour” of street life. It really shouldn’t be surprising that hustlers gravitate towards hoopers. It’s a relationship that stretches back for years and years.

Singleton was also able to give us an insight into the life of the young, black athlete from multiple angles. He explored the aforementioned urban plight through Ricky Baker in “Boyz N The Hood”. The ending to that story is all too common in our communities. But he showed us a different, more complex journey in “Higher Learning”. There he showed us the struggle of an African American student athlete, Malik Williams, trying to feel his way through life at a PWI (Predominantly White Institution). This to me, is a much more telling expose’ of the underlying hideousness of the trials and tribulations our young men and women face when they leave the familiarity of their neighborhoods and schools with mostly black faces and venture into a world that is hesitant to accept them and sometimes outright refuses to do so.

Black athletes at big schools are in a very weird space. There is the inescapable unpleasantness of the fact that many of the people going to your games and cheering you on are racist. Sure, they appreciate what you contribute on the field/court but at the end of the day, they still wouldn’t be your roommate. And even beyond that, they will treat you cordially and with some measure of “respect” because they feel like you’re not one of “those” black people. You’re special. A black kid on an athletic scholarship is viewed differently than a traditional student. Jane Doe with the 4.0 will always be viewed as an affirmative action acceptance who unrightfully took the spot of a more deserving white student as opposed to Johnny who averaged 40 pts per game in high school. He’s somehow different.

But the commonality in the perception of the two by their white counterparts is that neither would be at the school if not for extenuating circumstances. This is extremely ironic given the fact that we have Aunt Becky and Felicity Huffman bribing their kids into school. In Higher Learning Malik faced outward racism, struggled to find his place and ultimately experienced tragedy. I often think about this movie when the conversation surrounding why black athletes should abandon HBCU’s in favor of more notable PWI’s arises. We’re not talking about the Zion Williamson’s of the world. No one would ever do anything to jeopardize him at Duke. What about one of those other guys though? What do you think the story would be if Tre Jones went to North Carolina A & T while being recruited by Duke? Malik’s story is common and kudos to Mr. Singleton for bringing it to light. It should be a lesson to black athletes. Pick a school where you can live comfortably, void of sports. I’m sure Malik would have preferred attending another school where he was treated better over the prestige of Columbus’ track team.

John Singleton will be sorely missed in the industry and by those who were able to enjoy his work. He was a brilliant storyteller and showcased our reality to the world. He beautifully meshed three facets of our lives into cinematic excellence. The symbiotic relationship of hip hop, sports and urban culture was masterfully interwoven through his projects and he was able to somehow make it relatable to everyone who was watching. Continue to R.I.P. Mr. Singleton and may your work inspire the next great one.